As we enter a period of lower growth globally, investors have given higher valuations to companies that can achieve consistent growth. This seems logical, but are we in danger of overpaying?

That is a legitimate concern. But there is a way to avoid overpaying, in our view. Investors must apply a stringent analytical process to derive a fair value for the level of growth that a company can sustain over the coming years. After all, what good is owning a growth company in a low-growth world, if paying too lofty a multiple means that its stock price could be hit by the slightest bump in the road?

Three Steps to Estimating Value

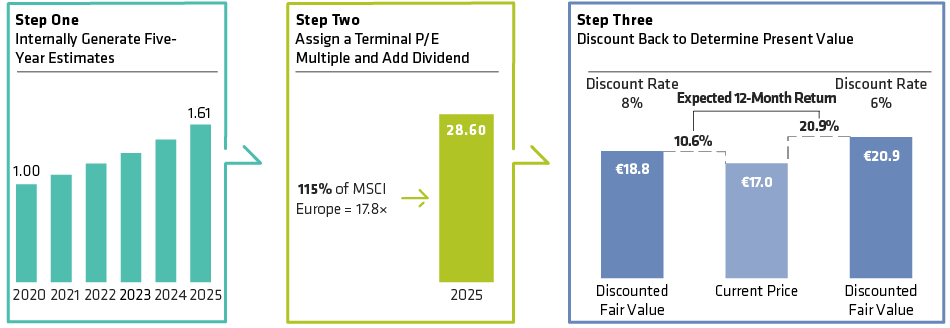

Assessing value starts with growth forecasts. Step one is to build a five-year model of a company’s growth prospects that best reflects factors including the nature of its business, prevailing market conditions and the competitive environment. This gives us an earnings number in five years’ time.

The next step is to consider what multiple the market will likely attach to those earnings, which is almost always lower than the current value. We take the earnings number, multiply it by the company’s prospective value, and add dividend payments to determine a total value five years forward.

Then, we discount that number back to today to derive a current target price. The discount rate is the required rate of return we believe is necessary to justify an investment. This discount rate is composed of: a risk-free rate, usually the 10-year government bond yield; an equity risk premium, which is the excess return required by equity investors to justify the increased risk of owning a stock over a bond; and finally, a stock-specific risk to reflect the differing nature of companies.

Conservative Multiples Are Vital

Based on our experience, this valuation method works in various market environments. For it to be effective, we believe relatively conservative multiples should be assigned to companies and the discount rate should also reflect normalized conditions. However, in a world of consistently low growth and exceptionally low interest rates, it may be appropriate to consider whether our discount rates are too high.

Consider the following example of a high quality European staples company. Over the next five years, we believe this company can grow its earnings by about 10% per year, made up of a combination of 5%–6% revenue growth and 1%–2% margin improvement, some acquisitions and some buyback accretion. When we add in its 2% dividend yield, we believe the stock’s total value in five years’ time will be about 65% higher than today.

For this company, we currently use a very conservative discount rate of 8%, made up of a risk-free rate and an equity risk premium. Given the company’s stability, the nature of its business and its rock-solid balance sheet, we don’t believe it requires a high stock-specific risk premium. Historically, the 8% reflects a risk-free rate of between 2% and 4% and an equity risk premium of between 3.5% and 5%.

But does that make sense today? With European bond yields near zero or even negative, the 8% discount rate in our example is made up almost entirely of an 8% equity risk premium. In today’s uncertain environment, perhaps a higher equity risk premium is warranted. But at 8%, the discount rate is about twice the historic level, which seems overly prudent for such a stable business.

Lowering the Discount Rate Leads to a Higher Target Price

Why does this matter? Because it significantly changes the target price. Using an 8% discount rate, the fair value of the company today is broadly in line with its current price, suggesting that the expected return over the next 12 months would be broadly in line with earnings growth—approximately 10%. However, when using a 6% discount rate—still reflecting a historically high equity risk premium—the fair value of the company is more than 12% higher, offering a potential return of almost 23% (Display).