-

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

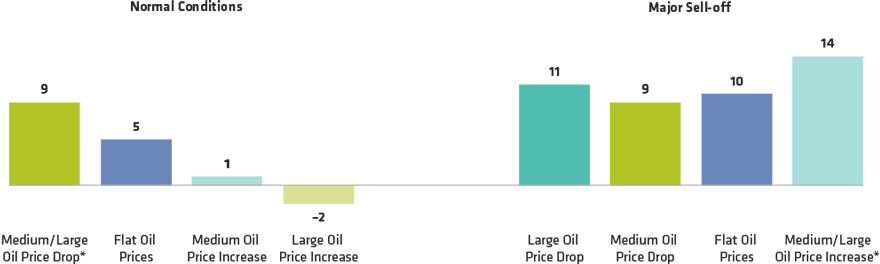

Don’t Rely on Cheap Oil to Power Equity Markets

One-Month Forward Equity Returns (%)

As of November 14, 2018

The colored bars represent the path of West Texas Intermediate oil prices over the past 12 months. A “large” drop or increase is between 1.5 and 2.5 standard deviations from the mean, a “medium” drop or increase is between 0.5 and 1.5 standard deviations from the mean, and flat is between –0.5 and 0.5 standard deviations from the mean. A “major selloff” is defined as the point when oil prices dip 15% below their five-year average, and normal conditions are anything above that.

*Due to a small number of instances of a large move in oil prices under these two scenarios, the medium and large categories were combined into one.

Source: AllianceBernstein (AB)

Sharat Kotikalpudi is the Director of Quantitative Research in the Multi-Asset Solutions Group at AB, specializing in systematic macro strategies; he leads the group's quantitative research in directional and cross-sectional strategies across developed and emerging markets within equity futures, currencies, rates and commodities. He is also a Portfolio Manager of AB Systematic Macro. Kotikalpudi joined AB in 2010 as a quantitative analyst on the Dynamic Asset Allocation team, where he helped to design and develop the quantitative toolset used in the group’s asset-allocation strategies. He holds a BE in electronics and communication engineering from the Manipal Institute of Technology, India, an MA in mathematics of finance from Columbia University and a PGDM from the Indian Institute of Management Calcutta. Location: New York