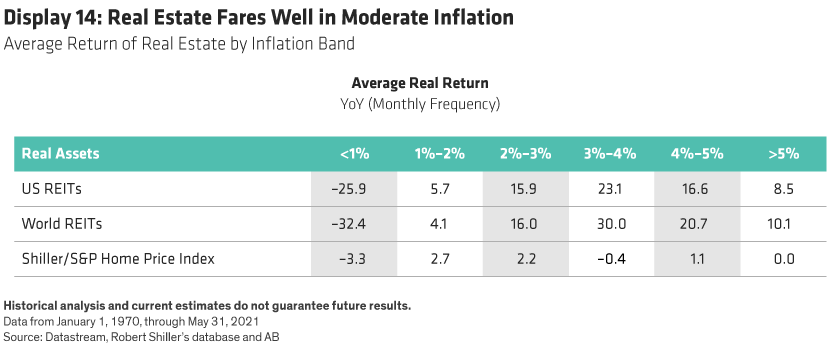

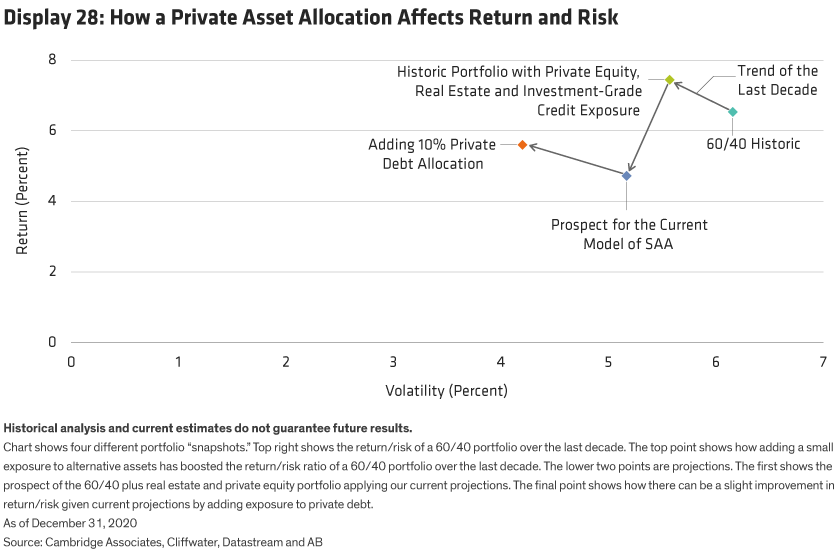

An increase in the strategic outlook for equilibrium inflation strengthens this case even more. Part of the inflation aspect relates to specific private assets that may be effective inflation hedges, such as real estate and infrastructure. But higher inflation is also likely to further erode overall expected real returns on a cross-asset portfolio, and it makes high-grade bonds less effective diversifiers of equity risk. These trends intensify the need for real returns and diversifiers.

A Closer Look at Liquidity (or Illiquidity)

Liquidity is a critical topic, but people mean different things by that term at different times, making it hard to define. Liquidity is the key to any comparison of public and private markets: it is, after all, probably the preeminent differentiating variable. In normal trading periods, liquidity in public markets has generally improved over the past decade (spreads have narrowed), but it’s more fragile for a host of reasons:

- Changing market structure, with the growth of high-frequency trading (HFT), the rise of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and evolving regulations leading intermediaries to take less risk

- A dearth of active-value investors

- Growing corporate debt

- The risk, at some point, of a transition from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening

There’s evidence [see Nataliya Bershova and Dmitry Rakhlin, “High-Frequency Trading and Long-Term Investors: A View from the Buy Side,” Journal of Investment Strategies 2, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 3–47.] that HFT liquidity dries up when volatility is higher. Moreover, the rise of ETFs has pushed more market volume into a shorter period around the market close rather than volume being dispersed throughout the trading day.

The general improvement in liquidity, most of the time at the expense of more fragile liquidity in times of crisis, could make tail risks more prominent across entire portfolios. The prospect of a market structure where even the supposedly liquid portion of a portfolio faces more illiquidity during economic stress has important implications: How much of a portfolio can be allocated to assets that may be unsellable at any price in crises? This risk must be built into governance structures for running portfolios. The possibility that public markets are more fragile can’t be easily shown, 1 but investment boards shouldn’t ignore it.

How much return should investors expect (or demand) for illiquidity risk? There have been a host of attempts to answer this. For example, Amihud (2002) 2 suggests that the illiquidity premium for illiquid versus liquid US equities is 1.3% annualized, using a model that compares long-horizon and short-horizon investors, with long-horizon investors spreading trading costs over longer time frames.

Ang, Papanikolaou and Westerfield (2014) 3 link the illiquidity premium to the time horizon over which an asset can be priced and sold. The return that an investor demands on an asset should increase if the interval over which it can be priced is longer. Moreover, uncertainty about the length of the liquidity interval is a key determinant of the returns that should be demanded. So, for an asset that can by priced on a one-year horizon, investors should demand a relatively small excess return but for an asset that can be priced only on a 10-year time frame, the required return would be higher.

How does this illiquidity premium compare with other fundamental risk premiums? In Dimson's paper for the Norway pension fund (Elroy Dimson, Antti Ilmanen, Eva Liljeblom and Øystein Stephansen, “Investment Strategy and the Government Pension Fund Global,” November 26, 2010), some of the most significant, very long-run risk premiums are estimated at 5.2% for the equity risk premium, 1% for the term premium, 0.4% for the credit premium and 6.1% for the foreign exchange carry premium. So, an illiquidity premium on the order of 1% isn’t insignificant from a return perspective. What’s more, most estimates of the illiquidity premium are derived from intra-asset-class returns, so they presumably underestimate a cross-asset-class illiquidity premium.

Ultimately, a discussion of liquidity needs to be tied to a time horizon, a topic too often regarded as an exogenous investing parameter. We think investors find it hard to change this view because it’s intertwined with questions of governance (often set up by a board or even public authorities through regulation) and career risk (that can’t be hedged).

But change is critical. In a world where maintaining risk-adjusted returns is more challenging, investors can’t afford to ignore any tools that improve their ability to meet liabilities. Therefore, we suggest that the time horizon of investment needs should be endogenous to the investment process—not regarded as written in stone and handed down by some higher authority.

At one level, this notion applies to all investment. There’s plenty of evidence that the time horizon of alpha decay varies across different strategies (Inigo Fraser Jenkins, Alla Harmsworth, et al., “Global Quantitative Strategy - Time-horizons in Finance: Bayesian trees for market allocation,” Bernstein Research, February 16, 2016), which is an even more critical consideration for a portfolio that spans public and private assets. Most investors need some portion of their portfolios in liquid assets to meet near-term needs, but pension plans, endowments, family offices and individual retirement savers can have sizable illiquid allocations. Maybe this didn’t matter over the past 30 years, when public markets were generating high returns and financial asset returns far surpassed real assets, but if that dynamic is changing (we think it is), the question of time horizon and liquidity matters very much.

What’s the Real Risk Exposure with Private Assets?

The forces driving flows into private assets are a microcosm of broader questions for the industry. At a deeper level, a critical aspect of the inflows is what they mean for the way investors consider risk. What’s the best allocation to risk, and which parameters are most appropriate for apportioning it across different portfolio components?

Investors can seek exposure to certain fundamental risks for alternative or private assets that, ideally, are distinct and uncorrelated to traditional equity and bond market risks, such as equity beta and duration. These fundamental risks or sources of return include:

- Illiquidity

- Quality

- Leverage

- Risk premiums (factor risk)

- Idiosyncratic alpha

It’s important that private assets genuinely carry risks along these dimensions—not just double down on risk exposures readily available via passive public investing. This is where innovation in the investment industry comes in. The price of buying factor risk has declined, and we think this will continue, so private assets must offer something over and above (and uncorrelated with) other risk premiums. Likewise, leverage might in theory be achievable in multiple ways, so merely being a vehicle for enabling leverage isn’t a sufficient excuse for investments like private equity.

A question must be asked: Are asset owners using private equity and other alternative investments to overcome what’s really a suboptimal governance arrangement? For example, consider asset owners who are only allowed limited leverage, or no leverage at all. If they’re allowed exposure to alternatives, they may be tempted to use it to obtain leverage—especially in a low-return, low-interest-rate environment like today’s. We see this as an incorrect motive for buying private assets or other alternative return streams, such as long/short investments.

One objective of our research is to make unashamedly normative statements. If some portion of private equity inflows are producing levered exposure to equity beta (or perhaps a permutation of the small-cap value factor), we think this misuses fee budgets and is an inefficient way to set parameters for risk budgeting. Instead, we suggest an honest confrontation with the governance structure. Changing these structures and investment policy statements is a lot harder, as it should be, but we see it as a more honest approach that’s likely to produce greater long-run benefits.

In recent years, we’ve developed an explicit framework for isolating the idiosyncratic alpha in active funds that invest in public equity and fixed-income markets (Alphalytics: Tearing Up the Rules on Active Management), return elements not readily available from passive-factor strategies. Processes like this are important in correctly apportioning risk and have gained immediate commercial importance with the collapse of passive factor fees in recent years (to just 4 basis points for US long-only equity factors in ETF format, for example).

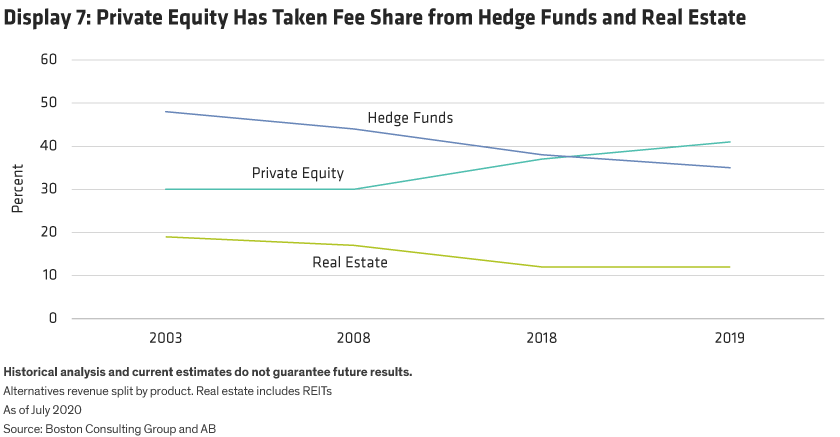

Now, these types of "passive" strategies for private investing return-stream components don’t readily exist today. However, the fee spread between active public funds and active private funds is stark, and the share of total fees paid has migrated to private equity. As a result, we expect that developing such alternatives to high-fee private assets will be a high priority for the asset-management industry, especially for private equity.

Another key aspect of the risk (and opportunity) of investing in private assets is selection alpha. To put it another way, the return dispersion among managers of private assets is much wider than for managers of public assets (Display 4). This presents an extra source of alpha if a fund selector can demonstrate a superior track record.