Hello, this is Inigo Fraser Jenkins from AllianceBernstein. In discussions with clients over the last year, perhaps unsurprisingly, a recurring theme was what impact should one expect from AI on the strategic outlook.

Our starting point for analyzing this is considering how artificial intelligence, or AI, interacts with other major forces. As we have explained in other research, the combined effect of deglobalization, demographics and climate change point to higher inflation and lower real growth.

Seen in this light, AI is the one force that potentially points in the other direction. Evangelists for AI would point to its ability to potentially raise productivity and hence growth.

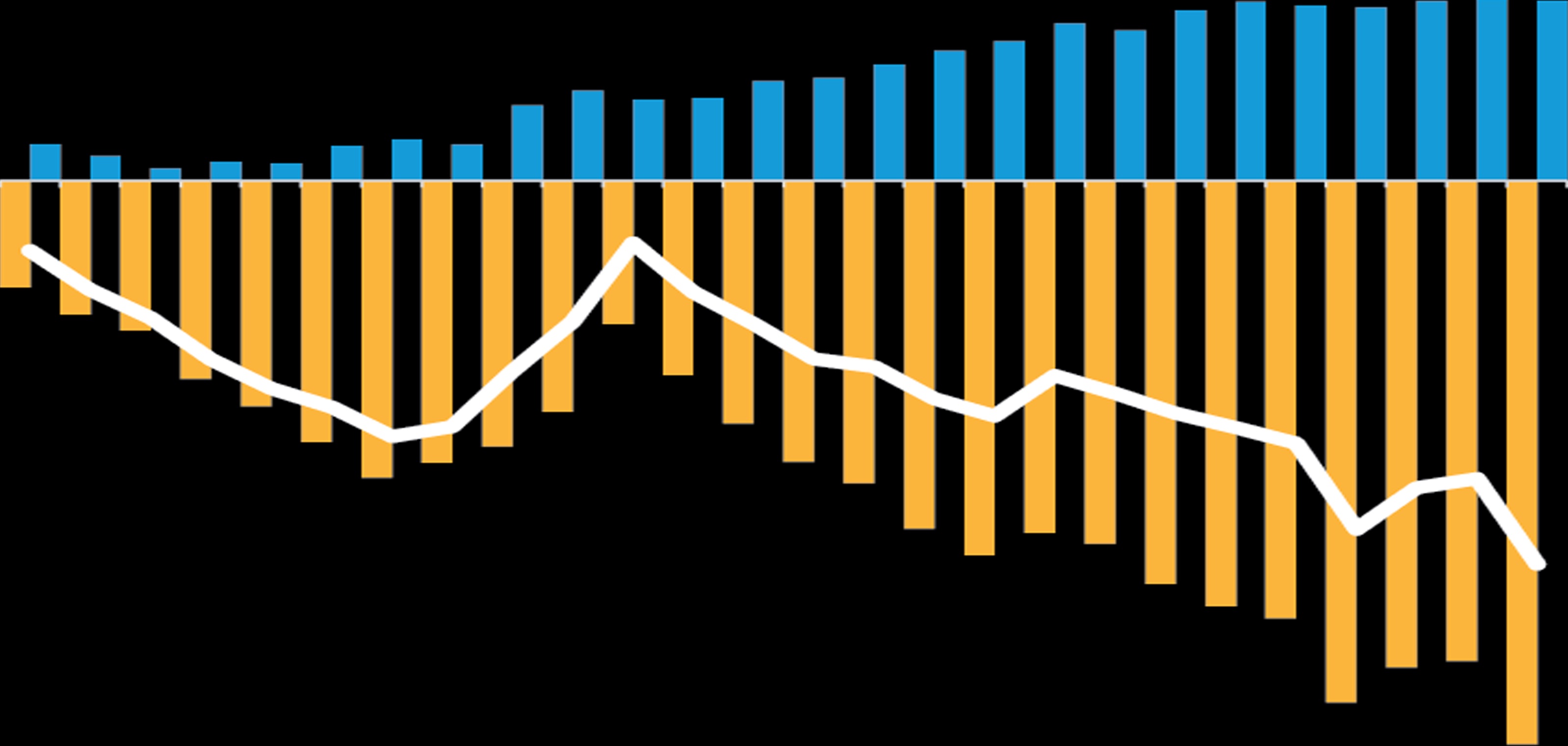

We simply think it is not possible to make a forecast for the aggregate productivity improvement of AI at this stage. Instead, what we can do is reverse-engineer the problem and ask: What would it have to achieve in order to counteract the combined effect on growth of the other forces? We estimate that AI would have to raise productivity growth by 1.5% per annum to do this.

Is this achievable? Since the war, the peak-to-trough change in productivity growth has been on this scale, so there is evidence that it is doable in theory. However, such a change is also at the top end of the historical range, so we would be uneasy in making such a productivity jump our central assumption.

AI certainly feels like a significant technological step. However, the last 20 years have seen considerable investment in automation, not least in the build-out of the internet. Yet despite this, there has been no discernible rise in the productivity of labor. Maybe this is a measurement problem, but proponents of AI being a panacea for growth need to explain why it is different this time.

On the negative side of the ledger, there is much discussion about whether AI destroys jobs. Corporates are very much in the driving seat, determining what AI is developed and released. Governments do not seem to get a look in—so far, at least. In our note, we show that the industries where jobs are most at risk are also the ones with the lowest unionization rates. This implies labor may have relatively weak bargaining power. Conversations about AI often lead from here to a discussion of universal basic income and what such a step would mean for inflation, government debt and, indeed, for the future of retirement.

Our work also discusses the more insidious effects of AI. These are the potential to widen wealth disparity, increase uncertainty around geopolitical tension, and raise profound questions about the future of democracy and elections when a majority of internet content is not human-generated. These are things that markets struggle to price, but they do need to be considered when laying out a strategic view.

We think that any truly strategic discussion of AI also needs to grapple with the deeper questions raised by the technology. These are the epistemological issues related to how it affects the way we attain knowledge. One strand of this is the contrast between prediction and explanation. AI tools give us the potential in some domains to make predictions with a new level of accuracy. However, can it be said to explain in any traditional sense? We have heard the view expressed that explanation is overrated, but we would strongly disagree. Likewise, there is a critical issue philosophically, socially and politically about the meaning of truth.

The advent of AI is sometimes compared, in an economic sense, to the invention of the steam engine, given its potential to lift productivity. However, the invention of the printing press may be a more apt technological analogy, given its impact on knowledge. What direction AI takes us on this topic is, at the moment, too hard to discern.

The bottom line is that AI can perhaps mitigate some of the downward forces on real growth rates, though we would still expect equilibrium inflation to rise and real growth to fall. The potentially more harmful effects of AI are things that markets find hard to price and are long term in nature. Nevertheless, they also need to be part of the discussion.

Thank you for your time.

Productivity, Democracy, Power and Truth: The Influence of AI on Markets

18 July 2024

4 min watch

About the Author

Inigo Fraser Jenkins is Co-Head of Institutional Solutions at AB. He was previously head of Global Quantitative Strategy at Bernstein Research. Prior to joining Bernstein in 2015, Fraser Jenkins headed Nomura's Global Quantitative Strategy and European Equity Strategy teams after holding the position of European quantitative strategist at Lehman Brothers. He began his career at the Bank of England. Fraser Jenkins holds a BSc in physics from Imperial College London, an MSc in history and philosophy of science from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and an MSc in finance from Imperial College London. Location: London