Hello I’m Inigo Fraser Jenkins and in this video I discuss some of the key investment conclusions from our recent book review essay called Machines, Democracy, Capitalism and Feudalism.

This is focused on the big questions that come up in discussions of AI and contemporary capitalism and what this means for the strategic outlook for investors. We do this via discussion of some recently published key books on these topics.

Skidelsky’s “Machine Age” is concerned with the impact of AI on labour. Pessimists argue that AI will wipe out jobs, while optimists point out that all the waves of automation since the Industrial Revolution have not led to structurally higher unemployment. There are still many jobs available despite countless ones having been automated away.

Skidelsky discusses Keynes’ forecast that by 2030 people would only need to work 15 hours per week. Skidelsky suggests there are three reasons why this forecast was so spectacularly wrong. First, people are not content to live today at a 1930s real standard of living. Second, work is not only a cost but also gives meaning. And third, the gains from productivity improvements have not evenly been shared, a topic that reappears in most of the books we discuss here.

While there was no overall increase in structural unemployment during the industrial revolution, it took a century for productivity improvements to be reflected in wages for the working class.

Skidlesky discusses the extent to which capitalism has been an enabler of technological development, but he asks at what cost? He suggests that society may need to decrease its dependence on machines. This is echoed in Crary’s book Scorched Earth which rejects what he sees as an unsustainable trajectory of development.

Martin Wolf’s “Crisis of Democratic Capitalism” makes the claim that the combination of a market economy and liberal democracy is unsustainable in its current form. Again, this harks back to the unequal sharing of prosperity, which he concludes has contributed to the loss of trust in the notion of truth. His blunt conclusion is that laissez-faire capitalism is incompatible with democracy.

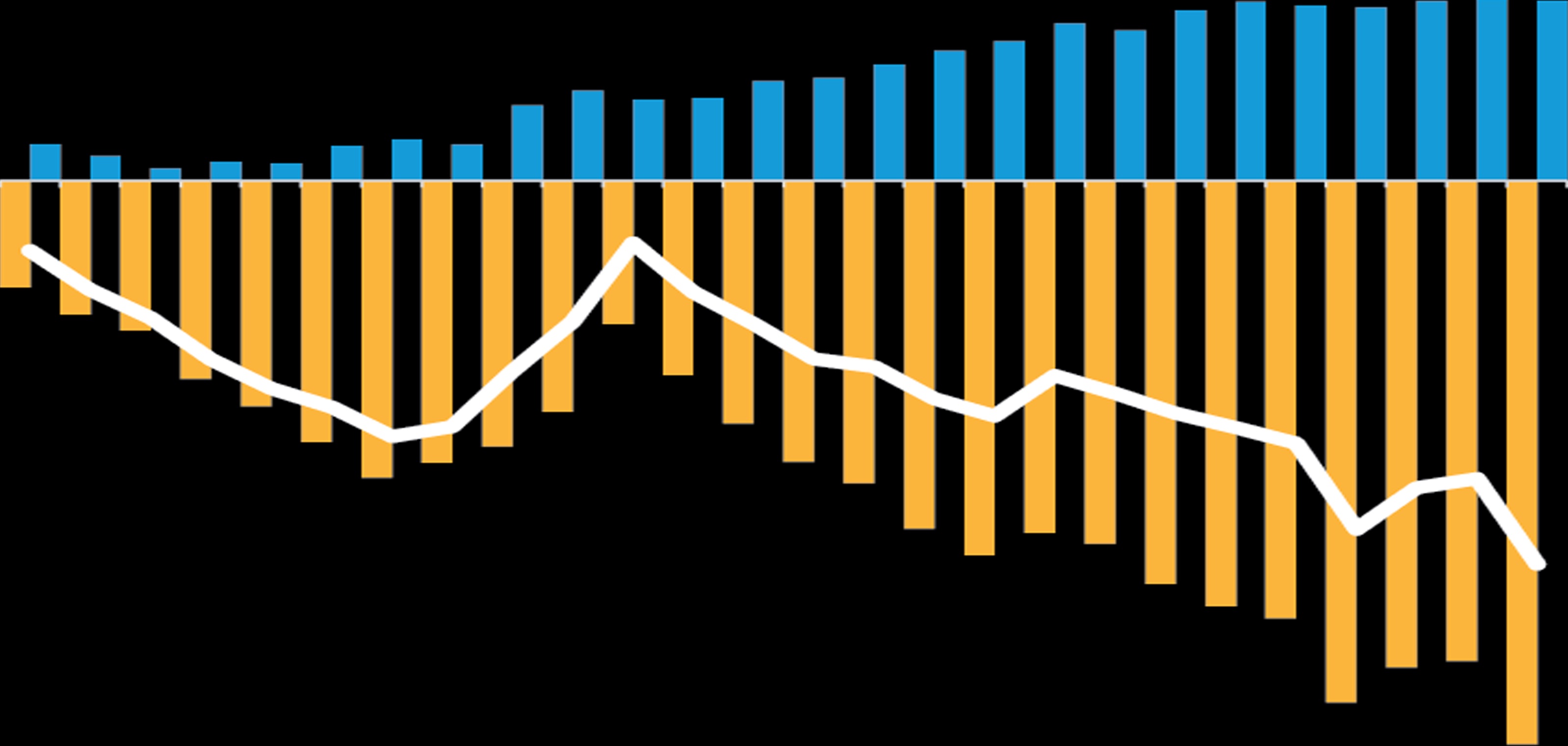

A theme through the book is the stalling of productivity growth of recent decades. Aside from this being a key focus for economics and politics, it is central to the way investors try to think about the structural consequences of AI. The book suggests that the increased financialization of the economy and emergence of winner-take-all markets are a political choice that has dampened competition.

If this is indeed the case, it implies that the techno-optimists may err if they assume that AI will structurally raise productivity in a new way.

Wolf also considers pension systems. He thinks the demise of defined benefit schemes was always inevitable as employers are problematic providers of long-term income promises. But with defined contribution systems there needs to be a way to allow them to have a large allocation to real assets, such as in collective DC.

Coming at these topics from a more Marxist angle, we consider is Technofeudalism by Yanis Varoufakis. His controversial assertion is that capitalism is now dead. He means this in the very specific sense that profits and competition no longer run the show. The only irony he points out is that the end of capitalism, as he puts it, was not brought about by organized labour, but by the privatization of the internet by Big Tech and the policy decision to lower the cost of capital.

Digital platforms might appear to be capitalist entities but in fact are more similar to fiefdoms. He suggests that anyone committed to the idea of the market (with Varoufakis himself presumably not in that group!) should profoundly worry about the replacement of profit by rent.

What conclusions can investors draw from these topics? The role of competition in driving productivity is a key theme. We would argue that the combination of demographics and deglobalization imply that there is a downward path to expectations of real growth. The open question is whether AI can generate an increase in productivity sufficient to offset this. If a lack of competition does indeed hold back productivity, then just because the technology gets better it might not be enough.

The second big topic is one of distribution. The growth benefits of global capitalism of the last 30 years have been very unevenly shared. The extent to which AI makes this better or worse will depend a lot on the way that AI changes the labour market. The path taken by AI development and whether this differs from previous rounds of automation therefore matters greatly.

Another theme that comes from these works is to expect governments to play a much larger role in economies in future, compared to the norms of recent decades.

On pension allocation, we agree with Wolf that the combination of greater longevity and likely higher equilibrium inflation likely means that pension allocations have to migrate to real assets. But if growth is slower, or the distribution means that people are unable to save sufficiently then this presents challenges.

All of these topics imply a need to evolve strategic allocations.

Thank you for your time.