The US housing market is healthy, but some market participants worry it may be starting to heat up too much. We think that’s a mistake—and an opportunity. That’s because mortgages today have little in common with the risky loans made before the housing crisis.

The confusion, in our view, stems from how people assess the credit quality of today’s loans. Before investors and analysts buy a residential mortgage-backed security (RMBS)—or assign a credit rating to one—they naturally want to know something about the quality of the underlying mortgage loans and the potential for defaults. The easiest way to do that is by reviewing average credit statistics.

For instance, there are FICO scores, which assess the overall credit strength of borrowers. Loan-to-value (LTV) ratios compare the size of the loan to the value of the property. And debt-to-income ratios indicate how much of a borrower’s monthly income goes to debt payments.

The Problem With Averages

Here’s the problem with focusing on the top-level averages: they can be misleading. These credit statistics (and a few others) can tell you a lot about the probability of default for an individual mortgage loan. But when those same statistics are averaged across thousands of loans in an RMBS, they become less meaningful.

The really meaningful aspect of loan analysis is how the different credit metrics relate and interact to define the riskiness of individual loans. For instance, do borrowers with low FICO scores also have high LTV ratios, meaning weak credit and high debt? Or do they have strong credit and more debt? And how are the different risk levels distributed throughout the RMBS?

Piling Risk On Top Of Risk

The practice of having multiple high-risk red flags in an individual loan is known as risk layering. Some risk layering is inevitable; borrowers rarely have perfect credit. But even a small increase in the number of negative credit metrics in a loan pool can substantially increase default probability.

In other words, risk layering—not average credit metrics—drives RMBS performance. The more risk layering there is, the higher the chances of default and the greater the potential loss.

Before the housing crisis hit, non-agency RMBS had a lot of risk layering. After all, subprime lenders routinely originated interest-only loans and lent money to borrowers without verifying their income or even requiring a down payment. This is a big reason why so many underlying loans defaulted when the housing bubble burst. We estimate that about half the losses experienced by precrisis RMBS were driven by risk layering.

Battle Of The RMBS Vintages

Many casual observers might look at surface-level metrics on the new risk-sharing transactions from government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and assume that the underlying loans would default in large numbers if the US housing rebound were to reverse course. (Risk-sharing transactions are also known as Credit Risk Transfer securities [CRTs] and are issued under the names STACR by Freddie Mac and CAS by Fannie Mae.)

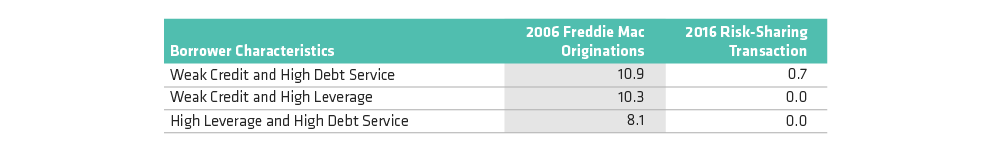

However, a closer look at the collateral suggests that isn’t necessarily true. Comparing precrisis RMBS to the new risk-sharing transactions (Display) shows that risk-sharing transactions have much less risk layering. We can see this by looking at the presence of various combinations of credit metrics that indicate riskier loans.