How are policymakers responding to these challenges?

Growth Target Remains Important

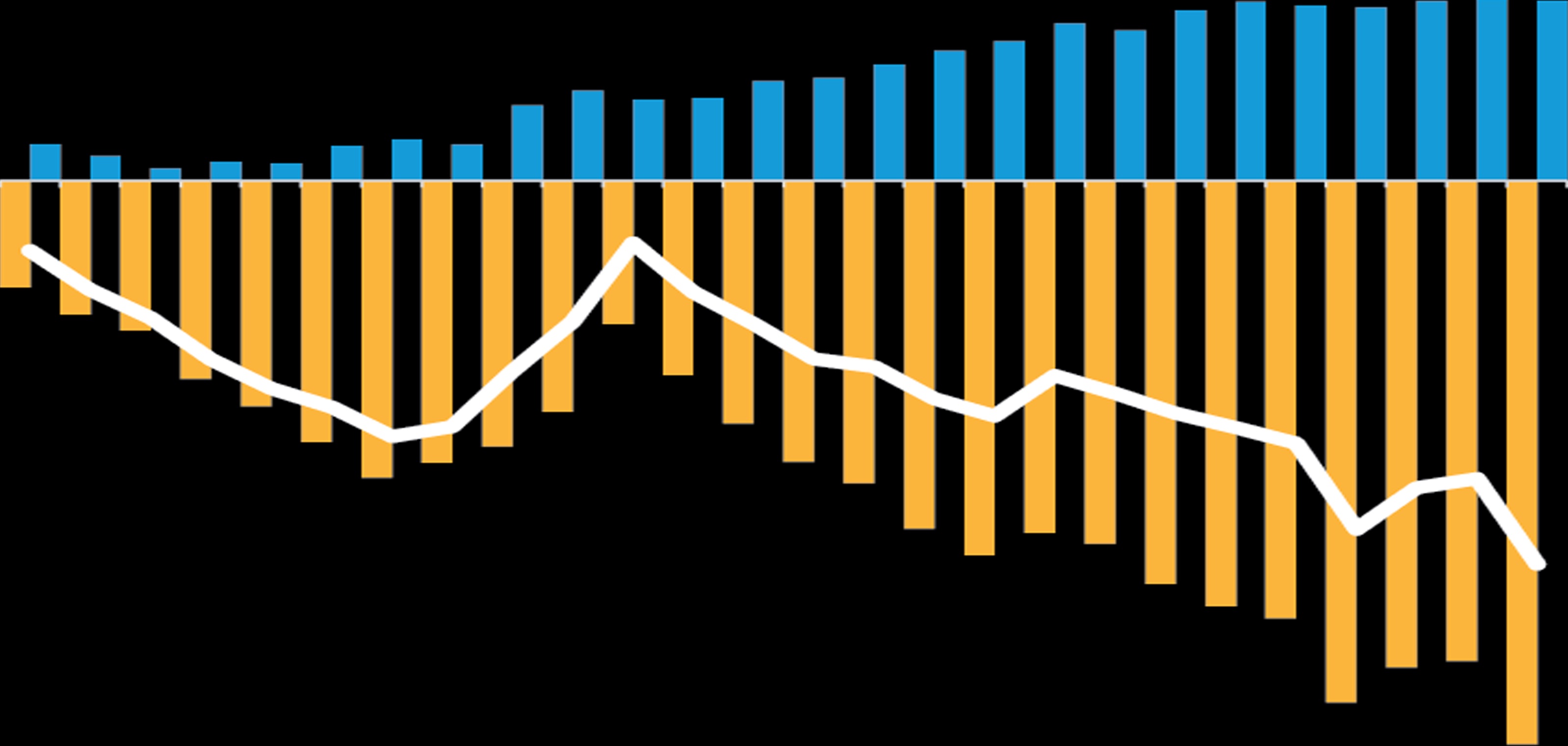

A unique attribute of Chinese economic policy is that it normally has an explicit growth target. (An exception was 2020; the target was dropped after the pandemic slowed the economy.) Based on first-half performance in 2021, the above-6% target for the year has been easily exceeded. Does that mean policymakers will accept low sequential growth for the rest of 2021?

No, precisely because there is a growth target. Low sequential growth rates in the third and fourth quarters of 2021 will make it harder for policymakers to meet next year’s annual growth target unless they can generate sequential GDP growth in 2022 at well above trend.

The importance of the growth target is underscored by the fact that the government aims to double income per capita by 2035 (we expect the 2022 GDP growth target to be either around 5.5% or between 5% and 5.5%).

The question, then, is not whether policymakers will support growth, but how they will do so.

Clearly, they won’t rely on the property sector, where the policy priority has been to promote stability by dampening activity through regulation. (The risk of collapse has been mitigated by flexibility at the local level to release some suppressed demand from first-time home buyers, with banks providing support through a modest pickup in mortgage lending.)

We think support for growth will come instead from a number of policy levers. The most significant will be expansionary fiscal policy, such as the acceleration of budgeted spending and local-government issuance of so-called special bonds, which support public investment.

Also, we expect the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to keep the currently mild policy rates unchanged, and to continue providing targeted liquidity to small and medium-size enterprises. While more emphasis on cyclical policy would be helpful for growth, we think large-scale stimulus is unlikely.

Against this background, we see reasonable prospects for fourth-quarter GDP in 2021 to rebound sequentially and for 2022 growth to be close to the potential growth rate (the rate at which the economy can grow over the medium term without generating excess inflation).

Given regulatory interventions in some business sectors this year, could our outlook for short-term growth be too optimistic? We don’t think so.

Not Just Growth, but Quality Growth

That’s because the government’s recent regulatory efforts and push for “common prosperity” have been largely misunderstood. They should be seen in the context of the government’s aim to achieve high-quality growth.

Recent interventions in the education and tech areas, for example, have been perceived as negatives for credit and equity markets, and for short-term growth. But they are better understood as part of a long-term strategy to promote high-quality growth by removing market distortions.

This is particularly important for China now, because its economy is at a key development stage, becoming more domestically focused with higher-value manufacturing, at a time of rapid domestic and external change (for example, the long-term effects of deglobalization on the country’s exports).

China is responding by pushing for structural reforms more aggressively than it has done in the past, to achieve a more sustainable and balanced growth trajectory.

Similarly, the recently revived common prosperity policy does not prioritize social equality at the expense of growth; rather, it envisages higher per-capita income and less inequality. One of the reasons for China’s relatively low consumption ratio, for example, has been widening inequality.

Over time, the common prosperity policy may help to narrow inequality, which would be a positive for household consumption—the organic growth driver mentioned earlier. This provides an example of how China’s various policy elements can connect with each other.