-

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

High Yield and Stocks

A Perfect Fit?

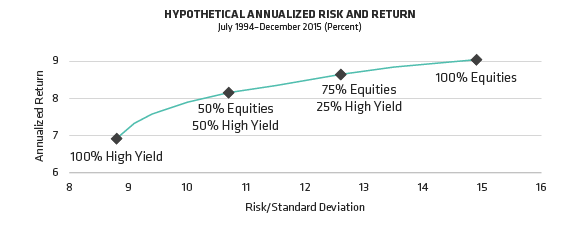

Diversification does not eliminate risk of loss. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Individuals cannot invest directly in an index.

As of December 31, 2015

High Yield is represented by Barclays US Corporate High Yield. Equities are represented by S&P 500.

Source: Barclays, Bloomberg, S&P and AB

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. An investor cannot invest directly in an index and its performance does not reflect the performance of any AB portfolio. The unmanaged index does not reflect fees and expenses associated with the active management of a portfolio.

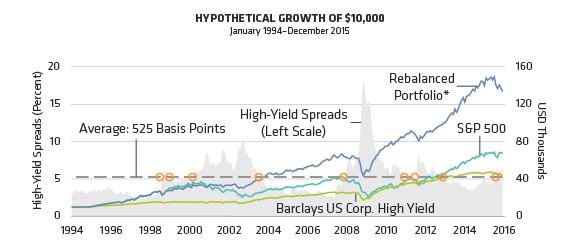

As of December 31, 2015; High-Yield spreads are represented by option-adjusted spreads (OAS) for Barclays US Corporate High Yield.

*The Rebalanced Portfolio tactically alternates between US High Yield and S&P based on a 525 b.p. spread decision rule.

Performance is based on spread levels and returns and assumes an investor began the period (1/1994) invested in the S&P 500 and made the following (9) transactions: sold the S&P and bought High Yield on 11/1/1998, sold High Yield and bought the S&P on 3/1/1999, sold the S&P and bought High Yield on 5/1/2000, sold High Yield and bought the S&P on 10/1/2003, sold the S&P and bought High Yield on 1/1/2008, sold High Yield and bought the S&P on 3/1/2011, sold the S&P and bought High Yield on 8/1/2011, sold High Yield and bought the S&P on 2/1/2013, sold the S&P and bought High Yield on 10/1/2015.

Source: Barclays, S&P and AB