-

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

Even As Defaults Rise, High Yield Should Stay Afloat

Jan 19, 2016

3 min read

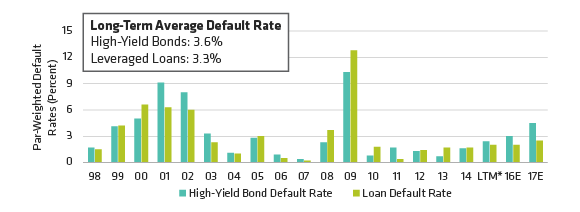

High-Yield Defaults Likely To Rise Somewhat

As of November 30, 2015

*Last 12 months

Source: J.P. Morgan

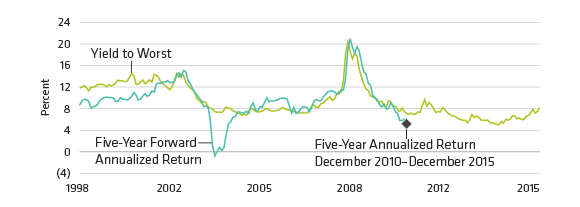

Yield To Worst Generally Predicts Market Returns Over The Next Five Years

Yield to Worst and Five-Year Forward Annualized Return

Historical analysis does not guarantee future results.

As of December 31, 2015

High yield is represented by Barclays Global High Yield.

Source: Barclays, Bloomberg, Credit Suisse and AB

About the Author